英語の後に日本が続きます。

Teramachi is an integral part of Takada’s rich 400-year history. It has helped shape the city’s character and identity. With its potential for promoting Takada, Teramachi remains largely undiscovered, overlooked rather than neglected. It is truly a hidden gem. What strategies can be implemented to bring Teramachi into the spotlight?

My previous post about the development of Takada Castle, its castle town, and Takada’s Teramachi served as an introduction to what I believe is the most crucial aspect of the Teramachi narrative. Are the temples adapting to maintain their spiritual significance while simultaneously developing a sustainable financial model? History and culture are important but how can temples sustain themselves in future, and remain relevant against the background of a declining population?

Demographics

Japan’s population is currently experiencing a significant decline, driven by a very low birth rate and an increasingly aging population. The current birth rate in Japan stands at 1.2, considerably below the replacement level of around 2.1 children per woman, indicating that the population is not naturally replenishing itself. Furthermore, there is a trend of people migrating from rural areas to larger cities which is also impacting Joetsu, including Takada.

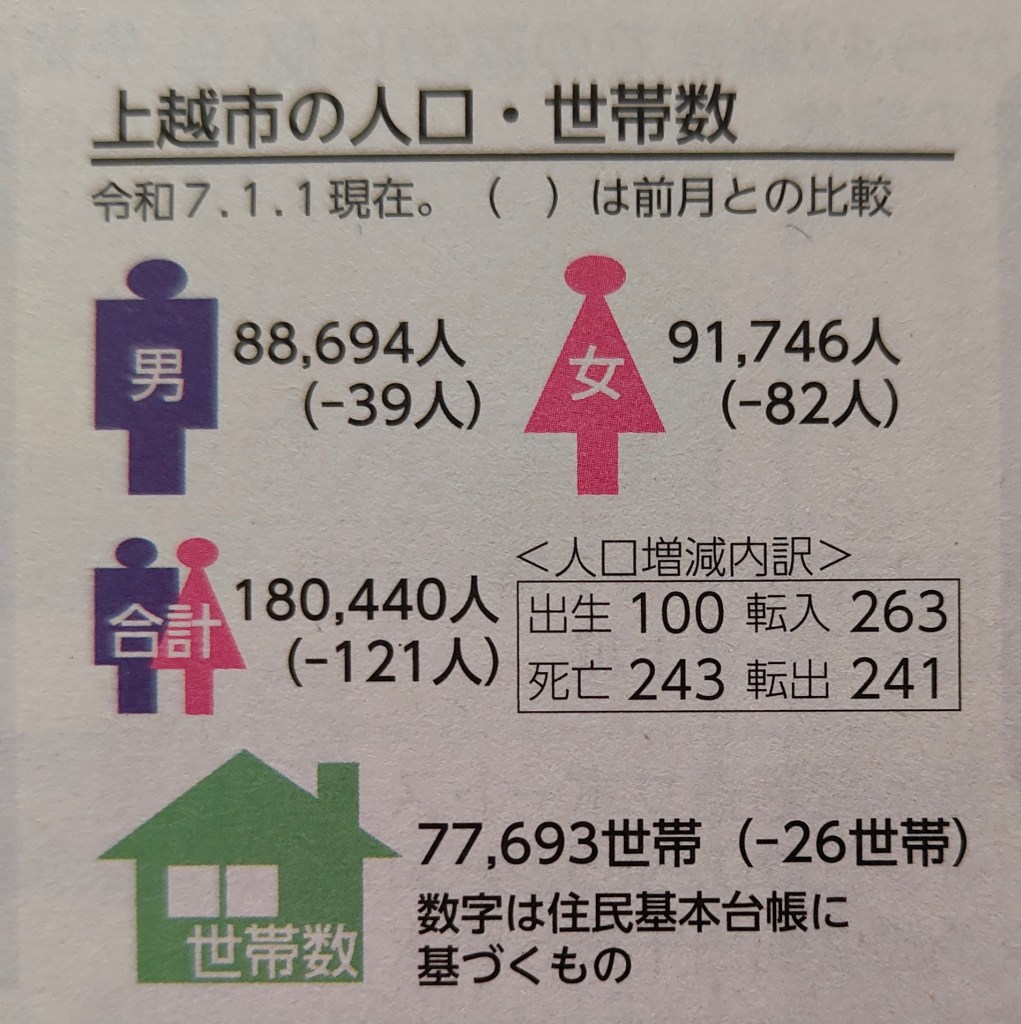

This decline will gradually undermine the economy and have a disastrous effect on social security in the long run. Experts estimate that over 40% of Japan’s 1700 municipalities could one day run out of residents and cease to exist. However, a decline is not unavoidable. Sixty-five municipalities have managed to create conditions that attract young families in sufficient numbers to be self-sustaining in terms of their population numbers. Still a small number but it is a first step in the right direction. Joetsu has unfortunately not joined this number yet and its population consistently declines by between 100 and 200 people per month.

This implies that temples, including those in Teramachi, are facing declining support from their communities. A significant concern is the potential shortage of Buddhist priests, particularly for smaller sects. This could lead to challenges in adequately serving all temples, potentially resulting in temple mergers or priests serving multiple locations.

Temple revenues and the Danka system

The financial stability of individual temples has depended heavily on the level of financial support they receive from their support groups. Against the background of Japan’s declining and aging population, the traditional “danka” system may no longer be sufficient to support temples financially.

The history of the danka system goes back to the Heian period. Initially it was a system of voluntary association of households with Buddhist temples that provided households with support for their spiritual needs in return for financial support.

During the Tokugawa period (1603-1868) the system was turned into a compulsory citizen registration network, based on Bakufu laws implemented in 1660. The main goal was to stop the spread of Christianity but the registration requirement soon developed into an instrument of broader social control. Households had to pay temples for registration and for maintaining their families’ register, thereby providing temples with an important, stable source of revenues.

The Tokugawa danka system was officially abolished in 1871 during the Meiji period, ending not only compulsory registration but also the associated revenues. The voluntary association of groups of supporters with temples, still referred to as danka, continued though, with the declining revenues to some extent being compensated by what is described as “funerary” Buddhism. Funeral services and maintenance of family graves became an important source of revenues for the temples, supplementing the voluntary contributions from the danka.

In 1872, Buddhism was no longer recognized as the state religion of Japan. Shintoism assumed this role, and the government concurrently fostered a strong anti-Buddhist sentiment, significantly hindering the funding of temple activities.

Following the war, the government abolished Shinto as the state religion, establishing freedom of religion and a separation of church and state. While this clarified Buddhism’s legal position, it did not address the significant financial challenges faced by numerous temples.

Temples have been forced to be more active in promoting community events and outreach programs to remain relevant to the community and to generate additional income. It led for instance to temples engaging in activities like running kindergartens. It has also forced priests to look for alternative, part-time or full-time careers to supplement their temple related income. One priest in Takada runs a coffeeshop with undoubtedly the best collection of jazz records in town. Many priests are employed as teachers. Another interesting example is Teramachi’s Chourakuji. If you look up the temple on Google Maps you will find an architect’s office in a very stylish, concrete building. The temple is at the back, integrated with the office.

How do the Teramachi temples interact with the secular world around it?

How is Teramachi organized and how does it interact with local government, local politicians. and with the Takada community?

Representation of interests of all temples in Teramachi is complicated by the presence of temples from six different sects. There does not seem to be anyone, or any organization that is able to speak authoritatively on behalf of all temples.

Temples within the same sect of course maintain close ties but do not get directly involved to any great extent in Teramachi’s relations with the world around it.

It is hard to see how the typical Japanese fragmentation and factionalism that currently prevents Teramachi from speaking with one voice can be overcome. Local politicians may play a role even though many are somewhat limited in what they can achieve by their membership of the danka of a temple of a particular sect.

Spirituality in Japan and a role for the temples

Buddhism and Shintoism have played a major role in shaping Japan’s spiritual practices whereas these have in turn influenced Japan’s cultural practices. Although the population’s involvement with Buddhism and Shintoism has declined, spirituality remains an important aspect of Japan’s culture and its identity.

There is an inherent need for spirituality but does the big city provide the same opportunities for spiritual practices as the country does? In the country side we are surrounded by symbols of spirituality, in the form of temples, shrines, and places for worship for natural phenomena, but Japan’s big cities lend themselves much less to spiritual practices. The declining population in rural areas raises concerns about the potential loss of an important aspect of Japan’s spiritual heritage. While it is difficult to quantify, it’s evident that an imbalance exists between the spiritual vibrancy of rural areas and that of major cities.

The postwar separation of state and religion prohibited direct government funding of temples and shrines. As a result, temples have become entirely reliant on independent revenue generation, beyond the stable but diminishing income from their traditional supporters (danka). This necessitates increased creativity and adaptability in their financial strategies.

Could Teramachi capitalize on this situation? Given Takada’s proximity to major urban centers like Kanto, it could potentially attract visitors from these areas. Religious tourism could play a significant role, offering spiritual experiences for city dwellers and intriguing foreign tourists. This influx of visitors could not only fulfill the spiritual needs of these individuals but also generate crucial revenue for many struggling temples. In turn, this economic boost would benefit Takada and contribute to the revitalization of Joetsu.

While direct financial support is prohibited, local governments can still play a crucial role in creating an environment that enables temples to achieve their goals. A prerequisite for this collaboration is a strong and cooperative relationship between Teramachi and the city government. This necessitates a unified voice representing the collective interests of all Teramachi temples to effectively advocate for their needs and engage in constructive dialogue with the city.

Digitalization – welcome to the 21st century!

Digitalization is a critical area for improvement. Many temples still rely on outdated communication methods, such as fax, to interact with their supporters (danka). While the older generation may be less familiar with digital means of communication, their numbers are dwindling, and younger potential supporters and tourists increasingly expect to find information and engage with temples through social media channels.

Religious tourism

Expanding commercial activities is crucial to supplement declining income from traditional sources like danka and funeral services.

Recognizing the growing interest in temple visits among both Japanese and international tourists, temples, or ideally groups of temples, must explore creative and realistic revenue-generating opportunities. Potential ventures include zazen, temple stays, temple cuisine experiences, guided tours showcasing temple treasures, cultural lectures, light shows, online sales of temple-related goods, yoga classes, concerts, exhibitions, unique venues like a Buddhist cafe or bar, and walking or cycling tours.

A well-defined marketing strategy is paramount for success. This plan should incorporate a strong partnership with professional travel agencies to effectively reach domestic and international target audiences and manage the logistical aspects of these commercial ventures.

Conclusion

Teramachi should be recognized as one of the unique features of Takada, along with the Goze of Takada, the gangi-dori and machiya, the castle, the lotus ponds, and the cherry blossom of Takada Park. I hope that by putting forward these suggestions and comments, I can contribute to the concrete steps that are needed to ensure the long-term viability of Takada’s Teramachi.

高田・寺町 Part 2

寺町の新たなビジネスモデルに向けて?

寺町は、高田の400年にわたる豊かな歴史の中で重要な役割を果たしてきました。街の個性やアイデンティティを形作るうえで欠かせない存在です。しかし、高田の魅力を発信する可能性を秘めながらも、寺町は今もなおあまり知られていません。決して忘れられているわけではないものの、その価値が十分に認識されていないのです。まさに”隠れた宝石”といえるでしょう。では、寺町の魅力を広く伝えるために、どのような戦略を取るべきでしょうか?

前回の記事では、高田城の発展や城下町、そして高田の寺町について紹介しました。今回は、寺町の未来にとって最も重要な側面に焦点を当てたいと思います。それは、寺院が精神的な役割を保ちつつ、持続可能な経済モデルをどのように確立していくのかという点です。歴史や文化の継承は大切ですが、少子高齢化や人口減少が進むなかで、寺院はどのように自らを支え、地域社会にとって意義ある存在であり続けることができるのでしょうか?

人口動態

現在、日本の人口は大幅に減少しており、その主な要因は極めて低い出生率と急速な高齢化です。日本の合計特殊出生率は1.2と、人口を維持するために必要とされる2.1を大きく下回っており、自然増加が見込めない状況にあります。さらに、地方から都市部への人口流出も進んでおり、高田を含む上越市にも影響を及ぼしています。

この人口減少は経済に深刻な影響を与え、長期的には社会保障制度にも大きな打撃を与えると考えられています。専門家の推計によれば、日本全国にある約1,700の自治体のうち、40%以上が将来的に無人化し、消滅する可能性があるとされています。しかし、この流れは決して不可避ではありません。現在、65の自治体は、若い世代を惹きつける施策を実施し、人口を維持できるだけの世帯数を確保することに成功しています。まだわずかな数ですが、持続可能な地域社会の実現に向けた第一歩といえるでしょう。残念ながら、上越市はまだこの動きに加わっておらず、毎月100〜200人の人口減少が続いています。

このような状況は、寺町の寺院を含む仏教寺院の運営にも影響を及ぼしています。特に懸念されるのは、地域社会からの支援の減少により、僧侶の不足が深刻化する可能性があることです。特に小規模な宗派では、この問題が顕著になると考えられます。その結果、寺院の統廃合や、一人の僧侶が複数の寺院を掛け持ちするといった形が一般化するかもしれません。

寺院の収入と檀家制度

個々の寺院の財政的安定は、これまで檀家(だんか)と呼ばれる支援者グループからの経済的支援に大きく依存してきました。しかし、日本の人口減少と高齢化が進む中で、従来の檀家制度だけでは、寺院の経営を維持することが難しくなってきています。

檀家制度の歴史は平安時代にさかのぼります。当初は、仏教寺院と世帯が自主的に結びつき、寺院が世帯の精神的な支えとなる代わりに、経済的な支援を受けるという形でした。

しかし、江戸時代(1603〜1868)に入ると、檀家制度は1660年に施行された幕府の法令によって強制的な戸籍管理制度へと変化しました。これは、キリスト教の拡大を防ぐことが主な目的でしたが、やがて社会統制の手段へと発展しました。すべての世帯は特定の寺院に所属することを義務付けられ、登録料や家族の記録維持費を支払う必要がありました。これにより、寺院は安定した収入源を確保できたのです。

この徳川時代の檀家制度は、明治4年(1871)に正式に廃止され、強制的な登録とそれに伴う収入も失われました。しかし、自主的な支援者グループとしての檀家制度は残り、その減少する収入を補う形で、「葬式仏教」と呼ばれる慣習が根付いていきました。葬儀の執行や墓地の管理は、檀家からの寄付と並ぶ寺院の主要な収入源となっていきました。

さらに、1872年には仏教が国家宗教としての地位を失い、代わりに神道が国の宗教とされました。この時期、政府は反仏教的な政策を推進し、寺院の財政状況は大きく悪化しました。

戦後、日本政府は国家神道を廃止し、宗教の自由と政教分離を確立しました。このことで仏教の法的地位は明確になりましたが、多くの寺院が直面していた深刻な財政問題を解決するには至りませんでした。

こうした状況の中で、寺院は地域社会とのつながりを維持し、新たな収入源を確保するために、より積極的に活動を展開する必要に迫られました。例えば、多くの寺院が地域のイベントを主催したり、幼稚園を運営するようになりました。また、多くの僧侶が副業や本業として別の職業を持つようになりました。

高田のある僧侶はコーヒーショップを経営しており、町で最も素晴らしいジャズレコードのコレクションを誇っています。また、多くの僧侶が教師として働くようになりました。

興味深い例として、寺町の長楽寺(ちょうらくじ)があります。Googleマップでこの寺を検索すると、コンクリート造りのスタイリッシュな建築事務所が見つかるでしょう。しかし、その奥に寺院が融合する形で存在しているのです。

寺町の寺院と世俗社会との関わり

寺町の寺院は、周囲の世俗社会とどのように関わっているのでしょうか?また、寺町はどのように組織され、地方自治体や地元の政治家、地域社会とどのように関係しているのでしょうか?

寺町のすべての寺院の利益を代表することは、6つの異なる宗派の寺院が存在するために非常に複雑です。現在のところ、寺町全体を代表して権威ある発言ができる個人や組織は存在しないように見えます。

同じ宗派の寺院同士はもちろん密接なつながりを維持していますが、寺町全体の対外的な関係には積極的に関与していないのが実情です。

この状況が変わる兆しはあまり見られません。日本社会に根強く残る派閥主義や分裂構造が、寺町が一枚岩として発言することを妨げています。

地元の政治家がこの状況を変える役割を果たす可能性はありますが、彼ら自身が特定の宗派の寺院の檀家であることが多く、その影響で行動が制限されることも少なくありません。

日本の精神性と寺院の役割

仏教と神道は、日本の精神的な慣習を形作る上で大きな役割を果たしてきました。そして、それらの精神的な伝統は、日本の文化的な習慣にも強い影響を与えています。現代では、仏教や神道に対する人々の関心は薄れつつありますが、それでも精神性は日本文化とそのアイデンティティの重要な側面であり続けています。

人間には本来的に精神性を求める気持ちがありますが、大都市と地方では、その実践の機会に違いがあるのではないでしょうか?地方には、寺院や神社、さらには自然現象を祀る場所など、精神性を象徴するものが数多く存在します。しかし、日本の大都市では、このような精神的な実践を行う環境が整っているとは言い難いのが現状です。地方の人口減少が進む中で、日本の精神的な遺産の重要な側面が失われるのではないかという懸念もあります。この問題を数値で測ることは難しいものの、地方と都市の間には精神文化の活力において大きな不均衡が生じているのは明らかです。

戦後の政教分離により、政府は寺院や神社に対する直接的な財政支援を禁止しました。その結果、寺院は伝統的な檀家制度による安定したものの縮小しつつある収入に依存するだけではなく、独自に収益を確保する必要が生じています。これにより、寺院にはより創造的で柔軟な経済戦略が求められるようになっています。

では、この状況を寺町が活かすことはできるでしょうか?

高田は関東圏の大都市に比較的近く、こうした地域からの訪問者を引きつける可能性を秘めています。宗教観光は、大都市に住む人々に精神的な体験を提供し、さらには外国人観光客の関心を引く重要な要素となり得ます。高田を訪れる人数の増加は、精神的なニーズを満たすだけでなく、経済的に困難さを抱える多くの寺院にとっても重要な収益源となるでしょう。そして、それは高田の発展や上越地域全体の活性化にもつながります。

地方自治体による直接的な財政支援は禁止されていますが、行政は寺院の目的達成をサポートする環境を整える上で重要な役割を果たすことができます。そのためには、寺町と行政の強固で協力的な関係が不可欠です。寺町の全寺院を代表する統一された声が必要となり、市と建設的な対話を行うことが求められるでしょう。

デジタル化 – 21世紀へようこそ!

デジタル化は、寺院が改善すべき重要な分野の一つです。現在、多くの寺院は依然としてFAXなどの旧来の通信手段に頼って檀家とやり取りを行っています。しかし、高齢者層は減少傾向にあり、若い世代の潜在的な支援者や観光客は、ソーシャルメディアを通じて情報を得たり、寺院と関わったりすることを期待しています。

現代のニーズに対応するためには、デジタル化の推進が不可欠です。寺院がより積極的にオンラインプラットフォームを活用することで、新たな支持者を獲得し、国内外の観光客に向けた情報発信の機会を増やすことができるでしょう。

宗教観光

伝統的な支援者である檀家や葬儀を行う事からの収入が減少する中で、それを補うために商業活動を拡大することが不可欠です。

日本国内外の観光客の間で寺院巡りへの関心が高まっていることを考慮すると、寺院が、あるいは理想的には複数の寺院グループが、創造的かつ現実的な収益を生み出す方法を模索しなければなりません。その可能性のある取り組みとしては、座禅体験や宿坊の提供、寺院の精進料理を味わう体験、寺宝を紹介するガイド付きツアー、文化講座、ライトアップイベント、寺院関連商品のオンライン販売、ヨガ教室、コンサートや展覧会の開催、仏教カフェやバーといったユニークな空間の提供、さらにはウォーキングツアーやサイクリングツアーなどが考えられます。

成功には、明確に定められたマーケティング戦略が不可欠です。そのためには、国内外のターゲット層に効果的にアプローチし、これらの商業活動の運営を円滑に進めるために、プロの旅行会社と強固なパートナーシップを築くことが求められます。

結論

寺町は、高田の特色の一つとして、高田の瞽女、雁木通りや町家、お城、蓮池、高田公園の桜と並んで認識されるべきです。これらの提案や意見を提示することで、高田の寺町の長期的な存続に必要な、具体的なステップに貢献できることを願っています。