英語の後に日本が続きます。

The goze of Takada formed a unique aspect of Joetsu cultural history. Goze (瞽女) were visually-impaired, female musicians traveling through the countryside, performing narrative songs, accompanying themselves on the three-stringed shamisen. The birth of a visually-impaired child imposed a large burden on a family and these children were therefore often trained to be music performers or masseurs/masseuses to lessen that burden and — more importantly — to allow them to be self-sufficient later in life.

Blindness would often be regarded as punishment for past misdeeds. Yet at the same time the goze were thought to possess certain spiritual powers and this superstition provided them with protection and respect.

The goze tradition existed throughout Japan, except in the northern part of Tohoku and in Hokkaido. It flourished during the Edo period but declined with the modernization of the Meiji era. As a result of elimination of the Tokugawa class structure, goze as well as their male counterparts (“todo”) lost their special place in society. In most of the country, goze associations disappeared altogether, except in Niigata where the goze continued to perform till the war. After the war the tradition survived in Niigata on a small scale only in Takada and Nagaoka until about 1970.

Although the death of Kikui Sugimoto (Takada goze) in 1983 and Haru Kobayashi (Nagaoka goze) in 2005 marked the end of the goze tradition, interest in the culture and music of the goze has been growing since the latter half of the twentieth century.

History of the Goze

There is evidence that blind male and female entertainers existed in the Muromachi period (1336-1573) but little is known about their activities and their status.

The myth about the origins of their art goes back much further. The goze traced their origins back to the daughter of Emperor Saga (809-823), Princess Sagami, who was blind herself. Her father wanted her to have a meaningful and independent life, despite her disability. He arranged for her to be trained in music and she became an accomplished performer. From her example a tradition was begun how blind people could live a productive life through artistic ability. However, there is no evidence to support this myth.

After a period of continuous warfare, Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa shogun, finally brought peace to Japan. Instead of wasting money on wars, money became available for improvement of infra-structure, creating much improved conditions and better security for traveling entertainers. From early Tokugawa, the existence of goze is well documented. In the Tokugawa period the goze as well as their male counterparts (“todo”) became subject to government oversight.

They were active from Kyushu in the south, to Fukushima and Yamagata in the north. They were prominent in Kanto, Chubu, and Hokuriku and maintained an especially strong presence in Echigo (Niigata).

In Takada they became active soon after the city was established in 1614.

Due to the modernization and changing perceptions of Meiji Japan, their numbers started to decline throughout the country and eventually disappeared altogether with one exception. The goze remained active in Niigata, a prefecture that was relatively isolated from the rest of the country, primarily in Nagaoka and in Takada.

Entertainment was provided by radio and television, medical care and the welfare system improved and after peaking during the Meiji period, also the number of goze in Niigata started to decline.

Post-war land reforms abolishing the feudal farming system resulted in elimination of the landlord class that had been important supporters of goze during their travels and the end of the tradition became a matter of time.

In the early 1970s the only goze still performing were Kikui Sugimoto (with Shizue Sugimoto and Kotomi Namba) in Takada, Kaneko Seki with a group of three in Nagaoka, Take Ihira (originally from Kashiwazaki), and Haru Kobayashi in Nagaoka.

Their life and music

Goze were generally from an agricultural background and had not had many opportunities for an education. The nature of their music was determined by their audience, the rural class that appreciated their music and was their support base.

The way in which goze were trained is described in Japanese as “shugyo” which is a combination of training with a specific way of life. Shugyo does not encourage personal expression and instills a sense of discipline that results in strength of character, a sense of purpose and uniformity in musical expression

Much of the Goze repertory has been lost but some of it – mostly from Niigata Prefecture — has been recorded.

Their repertory can be divided in several categories. The most important and characteristic ones were:

- Saimon matsuzaka: long strophic songs in a 7-5 syllable meter.

- Kudoki: Long strophic songs in a 7-7 syllable meter.

- Kadozuke uta: songs to make their presence known when going from house to house. The Niigata Goze used some unique songs for this purpose.

They also performed folk songs, songs belonging to different genres, like nagauta, joruri, hauta, kouta, and popular songs.

Their lives were physically and mentally demanding, requiring them to adapt to the goze lifestyle within a strictly hierarchical society, engage in rigorous musical practice, and endure grueling travel schedules.

The goze travelled around in their area most of the year, in small groups (3-4 goze) accompanied by a sighted person to guide them along the way (“tebiki”). Other than providing entertainment, the goze songs supposedly also made silk worms grow faster and for this reason they were often welcome guests. During their travels they would stay in “yado,” houses of prominent villagers where they often also performed.

The Goze of Takada

The city of Takada was established in 1614, with the construction of Takada Castle. Goze were active in Takada, but also in areas around the city, in Itoigawa, Naoetsu, Kariwa, and Kakizaki.

In 1922 there were still 14 houses and 44 goze in Takada but in 1944, there were only 3 goze families left: Noguchi, Ageishi and Sugimoto. After the war only the Sugimoto house, with Kikui Sugimoto as its head, her adopted daughter Shizu and their helper Kotomi Namba remained.

Following is a reconstruction — from various sources — of the number of goze in Takada, clearly showing the decline that set in during the Meiji period:

| 1681 | 26 Goze | Kubiki, Uonuma, Kariwa, Mishima |

| 1711-16 | 12 | Takada |

| 1742 | 20 | Takada |

| 1814 | 57 | 20 houses in Takada |

| 1884 | 69 | 17 houses |

| 1901 | 86 | 19 houses |

| 1922 | 44 | 14 houses |

| 1932 | 23 | |

| 1936 | 18 | 10 houses |

| 1944 | 3 houses | |

| 1945 | 3 | 1 house |

Unlike the Nagaoka goze, the Takada goze lived in the care of an “oyakata” (master) together in separate houses. The Takada goze houses were clustered around Higashihoncho. Each oyakata took care of several goze, trainees and a tebiki who assisted the goze during their travels.

The majority of Takada goze came from families in the area. Goze were prohibited from marrying and therefore had no children.

Organization of Goze in Niigata

Unlike their male counterparts, the goze did not have a national organization but were organized in regional associations of varying size. Such associations functioned as guilds, supporting goze in their daily lives, their careers, and their tours through the countryside but also protecting them against unwanted competition. In Niigata, the Takada Seijo and the Nagaoka Goze were influential but each was organized in a different way. Both groups had a strict hierarchical structure and their own set of rules.

The head of the Nagaoka Goze family assumed the name “Yamamoto Goi” upon her election. She would live in a goze family house in Nagaoka, from where she controlled the goze women who lived throughout the Chuetsu region.

The oyakata of individual groups of goze in Takada was required to own a property in Takada, where her group lived together, practiced and trained its apprentices. The most senior oyakata was elected “zamoto” to supervise and represent the Takada goze.

The Nagaoka goze traveled and performed mostly in the central part of Niigata, the Takada goze in the Kubiki area of Niigata (Joetsu) and Northern Nagano.

Their rules, the “Goze Shikimoku”

The Takada goze followed a set of strict rules, the “Goze Shikimoku,” probably modelled after the Shikimoku of the national association of todo which were recognized by the Tokugawa in 1634, and in amended form again in 1692. The rules for todo were initially valid for Edo but gradually extended to the rest of the country and covered a wider range of activities, including massage and Chinese medicine.

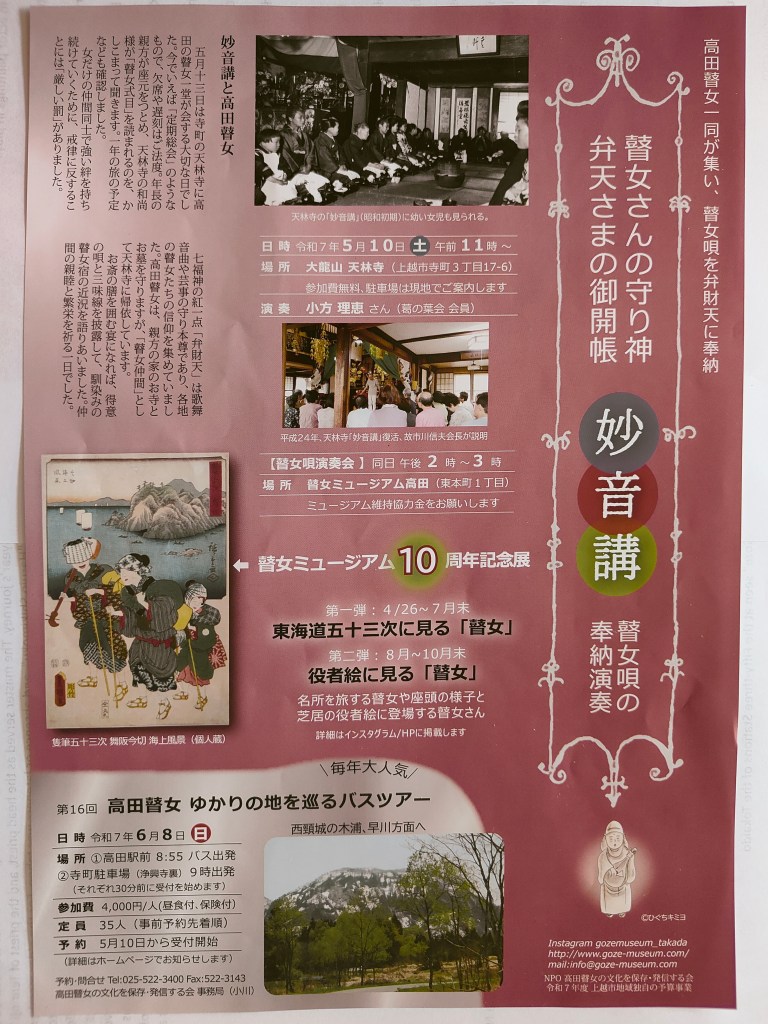

The shikimoku covered every aspect of goze life, including their day-to-day routine. Every year these rules were recited at a ceremony named Myoon-ko, celebrating Benzaiten, goddess of music. The Myoon-ko for the Takada goze was held annually on May 13 at Tenrinji, in Takada Teramachi, until 1939.

Attendance at the Myoon-ko required their timely return to Takada. Goze would know that the time for Myoon-ko was approaching by the smell of a particular flower, “botan,” the peony flower. Observance of the rules was important to maintain the high moral standards that in a way were a form of protection of the goze. Serious misconduct was punished by reducing the number of years of training credited to a goze, a harsh penalty given the importance of seniority in their hierarchy. The most serious misconduct was to have a relationship with a man and this could, depending on the circumstances lead to being expelled from the group.

To align their rules with modern thinking and the demands of the Meiji period, the Takada goze reviewed and adapted their regulations in the early 1900s and became a professional alliance (“dogyochu”).

The last Goze

It is always difficult to assign an exact date to the end of a tradition that fades gradually, but in the case of the goze, two names and two dates stand out: 1964, when Kikui Sugimoto completed her final tour of the countryside, and 1973, when Haru Kobayashi retired from touring. Fortunately, both continued to perform in concert settings afterward, allowing much of their music to be recorded.

Kikui Sugimoto

Kikui Sugimoto, the last master of a house for goze in Takada, was born in 1898 in what is now Higashinakajima, Joetsu. She lost her eyesight at age 6, and at age 7 she became an apprentice to Mase Sugimoto, the first head of the Sugimoto family. The Sugimoto house was located at Higashihoncho 4-chome in Takada, Joetsu. When Mase passed away, in 1932, Kikui took over from her as the head of the Sugimoto goze family.

Many goze were forced to give up their way of life, but Sugimoto continued with her adopted daughter Shizu and her assistant, Kotomi Namba. Her last tour was in 1964 when she visited Higashinakajima in Joetsu, her birthplace.

In 1970 she received the government’s Medal of Honor with Yellow Ribbon (黄綬褒章) in recognition of her services and in 1976 she was recognized as a Living National Treasure.

Kikui Sugimoto passed away in 1983. Her last words were: “I have forgotten the words to the song. Living on is pointless.”

Haru Kobayashi

Haru Kobayashi, the last of the goze was born in 1900 in present-day Sanjo, near the city of Niigata. At age 4 she started her training as a Goze under Fuji Higuchi. In 1915 she entered an apprenticeship with Sawa Hatsuji of Nagaoka. After Hatsuji’s death, she continued her studies under Tsuru Sakai. At age 33 she became a full-fledged Goze. She lived through difficult personal circumstances, and the war time, and she eventually went into retirement in a nursing home in Shibata in 1973. In 1977 she entered a nursing home for the blind, including former goze, “Yasuragi no Ie”, in Tainai.

After her retirement she collaborated in recordings of her goze songs.

In 1978 Kobayashi was recognized as a Living National Treasure, and in the following year she received the government’s Medal of Honor with Yellow Ribbon.

She still had some students including Reiko Takeshita. Naoko Kayamori became Kobayashi’s last student.

In 2005 she passed away at age 105.

The role of Tenrin-ji in the life of the Takada Goze

Tenrinji served as a spiritual and communal center for the goze. It was a place where they could gather, and participate in religious ceremonies. The temple provided a sense of community and support, reinforcing their shared identity and purpose.

Benzaiten, the goddess of music, was revered as the guardian deity of the goze. Tenrinji, a Soto Zen temple located in Takada’s Teramachi district, honors Benzaiten at an annual event known as Myōon-kō, held on May 13. All the Takada goze would attend this important occasion. After the sutra was recited and the deity was venerated, the goze’s rules were formally read aloud, followed by a performance and a banquet. This event was the most significant of the year for the goze. The annual event was discontinued in 1939 but revived in 1972 and held every year till 1980. In 1983 the Myoon-ko was celebrated again shortly after the death of Sugimoto Kikui with participation by Shizu Sugimoto and Kotomi Namba.

Renewed interest in Goze

The goze tradition largely disappeared across Japan in the early 20th century, with little effort made to preserve information about it. Although the tradition rapidly declined, paradoxically, interest in its preservation grew.

In Nagaoka and Takada, the tradition persisted until the mid-20th century, a time when there was a much stronger interest in preserving manifestations of Japanese folklore. The last generation of goze was not only still alive but also performing, allowing for interviews, and for sound and video recordings.

We should be grateful to a group of artists — including painter and writer Shinichi Saito, photographers Shoko Hashimoto and Hiroshi Hamaya, and writer Tsutomu Mizukami, whose Hanare Goze O-rin inspired the film The Ballad of Orin — as well as many others for their contributions in preserving the goze tradition.

Above all, we should acknowledge the key role that was played from 1932 onwards by Shinji Ichikawa. Ichikawa, who was born in Takada, was a disciple of the great Kunio Yanagita (1875-1962), considered the father of Japanese folklorism. Ichikawa, encouraged by Yanagita made the Takada goze his life’s work and was instrumental in getting many artists to take an interest in the life of the Goze. He was supported in his efforts by Keizo Shibusawa, grandson of Eiichi Shibusawa, who combined his role as Governor of the Bank of Japan and later Finance Minister with a strong interest in philanthropy and folklorism.

In 1953, Kasho Machida, a Japanese music scholar and critic, particularly known for his work on Japanese folk song recorded Take Ihira, a goze from Kashiwazaki. In 1954 Kikui Sugimoto, recorded a Saimon Matsuzaka. In 1969 she performed in the National Theater in Tokyo. During 1975-1979 she recorded an important portion of her repertoire in Joetsu. The last available recording of Haru Kobayashi was made in 1996.

Several women have more recently continued the tradition and are teaching and performing the goze repertoire, among them: Hirosawa Reiko, Kayamori Naoko, Kotake Eiko, Murohashi Mitsue, Ogata Rie, Takeshita Reiko, Tsukioka Yukiko, Yokokawa Keiko, and others.

The Goze Museum in Takada

The revival of interest in goze is centered around Takada’s Goze Museum, which opened in 2015. It is the only museum in Japan dedicated to preserving the history and culture of the goze. The museum is housed in a traditional machiya (townhouse). The original Asaya Takano machiya burned down in 1935 but was rebuilt in 1937, following its original layout. It was designated as a National Cultural Asset in 2012.

The museum’s exhibits include a documentary movie from the early 1970s describing the lives of the last surviving goze at that time, recordings of goze songs, a num ber of Shinichi Saito’s goze paintings, and photos by Shoko Hashimoto and others.

The museum is open on weekends, from 10AM to 4PM and is located at Higashihoncho 1-2-33, Takada, Joetsu (www.goze-museum.com).

高田の瞽女(ごぜ)

高田の瞽女は、上越地域の文化史において独特の側面を形成していました。瞽女(ごぜ)とは、視覚に障がいのある女性音楽家で、三味線を弾きながら物語性のある歌を歌い、農村部を巡って演奏していた人々のことを指します。

視覚障がいのある子どもが生まれると、その家族には大きな負担がかかりました。そのため、こうした子どもたちはしばしば音楽の演奏者やあんま(按摩)として訓練を受け、家族の負担を軽減するだけでなく、将来的に自立できるように育てられました。

盲目は、過去の悪行に対する罰と見なされることもありました。しかし一方で、瞽女は霊的な力を持っているとも信じられ、そうした迷信によって一定の保護や尊敬を受けることもありました。

瞽女の伝統は、東北地方の北部や北海道を除いて、日本各地に存在していました。この伝統は江戸時代に最盛期を迎えましたが、明治時代の近代化により衰退しました。徳川時代の身分制度が廃止されたことにより、瞽女やその男性版ともいえる「当道(とうどう)」は、社会の中での特別な立場を失ったのです。

全国の多くの地域で瞽女組織は姿を消しましたが、新潟県では戦争の時代まで活動が続けられました。戦後も、瞽女の伝統は新潟県内では高田と長岡で小規模ながら存続しており、1970年頃まで続いていました。

高田の瞽女・杉本キクイが1983年に、長岡の瞽女・小林ハルが2005年に亡くなったことで、瞽女の伝統は終焉を迎えました。しかし、20世紀後半以降、瞽女の文化や音楽に対する関心は徐々に高まってきています。

瞽女の歴史

盲目の男女の芸能者が室町時代(1336〜1573年)に存在していたという証拠はありますが、彼らの活動内容や社会的地位についてはほとんど知られていません。

その芸の起源に関する神話はさらに古くまで遡ります。瞽女たちは、自らも盲目であった嵯峨天皇(在位:809〜823年)の娘・相模内親王を起源とする伝説を語り継いでいました。父である天皇は、娘に障がいがあっても有意義で自立した人生を送ってほしいと願い、音楽の訓練を受けさせました。彼女は見事な音楽家となり、その姿が、視覚障がいを持つ人々が芸術的な能力を通じて生産的な人生を送るという伝統の出発点となった、とされています。しかしながら、この神話を裏付ける歴史的証拠は存在しません。

戦乱の時代が続いた後、初代徳川将軍・家康がついに日本に平和をもたらしました。戦争に使われていた資金が社会基盤の整備に回されるようになり、旅芸人たちが活動するための環境や治安が大きく改善されました。徳川時代の初期からは、瞽女の存在が文献にしっかりと記録されています。この時代、瞽女やその男性版である「当道(とうどう)」は、幕府の管理下に置かれるようになりました。

彼女たちは九州から福島・山形といった東北地方まで広く活動しており、関東、中部、北陸では特に盛んでした。中でも越後(現在の新潟県)では、非常に強い存在感を持っていました。

高田では、1614年に城下町として整備された直後から瞽女たちが活動を始めました。

しかし、明治時代の近代化と社会意識の変化により、全国的に瞽女の数は減少し、ついにはほぼ消滅しました。ただし一つの例外として、新潟県では瞽女の活動が続きました。新潟は他地域から比較的孤立していたためであり、特に長岡と高田でその伝統が守られました。

やがて、ラジオやテレビによる娯楽の普及、医療や福祉制度の改善により、瞽女の役割は減少。明治時代にピークを迎えた新潟の瞽女たちも次第にその数を減らしていきました。

戦後の農地改革によって封建的な小作農制度が廃止され、瞽女たちを支えていた地主層が姿を消したことで、彼女たちの伝統の終焉は時間の問題となりました。

1970年代初頭には、まだ活動していた瞽女はわずかに残るのみであり、高田では杉本キクイ(および杉本シズ、難波コトミ)、長岡では金子セキとその三人組、柏崎出身の伊平タケ、そして長岡のハルだけとなっていました。

瞽女の暮らしと音楽

瞽女たちは一般的に農村出身で、教育を受ける機会はほとんどありませんでした。彼女たちの音楽の性質は、農村の人々という聴衆に合わせたものであり、彼らが瞽女の音楽を評価し、支えていたのです。

瞽女の修行方法は日本語で「修行(しゅぎょう)」と表現されます。これは単なる訓練にとどまらず、特定の生活様式を伴う修練のことを指します。修行では個人的な表現はあまり重視されず、代わりに厳格な規律が身につけられ、それによって強い精神力、目的意識、そして音楽における統一感が育まれました。

瞽女のレパートリーの多くは失われてしまいましたが、新潟県を中心とする一部の楽曲は記録に残されています。

彼女たちのレパートリーはいくつかのカテゴリに分類できます。中でも最も重要で特徴的なのは以下の通りです:

- 祭文松坂(さいもんまつざか):7・5拍の音節パターンによる長い連作歌。

- 口説き(くどき):7・7拍の音節パターンによる長い連作歌。

- 門付け歌(かどづけうた):各家庭を訪問する際に、自分たちの訪問を知らせるための歌。新潟の瞽女はこの目的のために独自の歌を使っていました。

そのほかにも、民謡や長唄、浄瑠璃、端唄、小唄、流行歌など、さまざまなジャンルの楽曲を演奏していました。

瞽女の生活は肉体的にも精神的にも非常に厳しいものでした。厳格な上下関係のある社会での集団生活、過酷な音楽修練、そして長期にわたる旅に耐えなければならなかったのです。

瞽女たちは、ほとんどの期間を自分たちの地域を巡りながら過ごしており、通常3~4人の小さなグループで旅をしていました。彼女たちの移動には、「手引き(てびき)」と呼ばれる目の見える同行者が道案内として付き添いました。

瞽女は単なる娯楽を提供するだけでなく、その歌声が「蚕の成長を早める」とも信じられており、そのため農家から歓迎される存在でもありました。旅の途中では、「宿(やど)」と呼ばれる村の有力者の家に泊まり、その家で演奏を披露することも多くありました。

高田の瞽女(ごぜ)

高田の町は、1614年に高田城の築城とともに誕生しました。瞽女たちは高田の市内だけでなく、糸魚川、直江津、刈羽、柿崎など周辺地域でも活動していました。

1922年の時点では、高田にはまだ14軒の瞽女の家があり、合計44人の瞽女がいたとされています。しかし1944年には、瞽女の家はわずか3軒となり、「野口家」「揚石(あげいし)家」「杉本家」だけが残っていました。戦後には、杉本家のみが活動を続け、家元の杉本キクイと、養女のシヅ、そして手伝いの難波コトミの3人だけが残りました。

以下に示すのは、さまざまな資料をもとに再構成された、高田における瞽女の人数の推移です。この記録は、明治時代から顕著になった衰退の過程を明確に示しています。

| 1681 | 26人 | 頸城, 魚沼, 刈羽, 三島 |

| 1711-16 | 12人 | 高田 |

| 1742 | 20人 | 高田 |

| 1814 | 57人 | 高田20軒 |

| 1884 | 69人 | 17軒 |

| 1901 | 86人 | 19軒 |

| 1922 | 44人 | 14軒 |

| 1932 | 23人 | |

| 1936 | 18人 | 10軒 |

| 1944 | 3軒 | |

| 1945 | 3人 | 1軒 |

長岡の瞽女とは異なり、高田の瞽女たちは「親方(おやかた)」と呼ばれる師匠のもとで、専用の家に集団で暮らしていました。高田の瞽女の家々は、東本町周辺に集中していました。各親方は、複数の瞽女や見習い、そして旅の際に同行して案内をする「手引き(てびき)」を世話していました。

高田の瞽女の多くは、地元の家庭の出身者でした。瞽女には結婚が禁じられていたため、子どもを持つこともありませんでした。

新潟における瞽女の組織

男性の芸能者(当道)とは異なり、瞽女には全国規模の統一された組織は存在せず、地域ごとに異なる規模の団体として組織されていました。これらの団体は、いわば職業組合(ギルド)のような機能を果たし、瞽女たちの日常生活、芸能活動、農村部での巡業を支援するだけでなく、望ましくない競争から彼女たちを守る役割も担っていました。

新潟県では、高田の「高田清浄」と長岡の「長岡瞽女」が特に有力で、それぞれ異なる組織構造を持っていました。両者ともに厳格な上下関係を持ち、独自の規則を備えていました。

長岡瞽女の家元に選ばれた女性は、「山本ゴイ」という名を襲名し、長岡の瞽女家に居住しながら、中越地域全体に暮らす瞽女たちを統括しました。

一方、高田の瞽女たちは、個別のグループを統率する「親方」が必ず高田市内に住居を所有し、その家で弟子たちとともに暮らし、練習や修行を行っていました。親方の中でも最も年長で権威ある人物が「座元」として選出され、高田瞽女全体の監督と代表を務めました。

長岡の瞽女たちは主に新潟県中部を巡業範囲とし、一方、高田の瞽女たちは新潟県の頸城(くびき)地域(現在の上越市)や長野県北部を中心に活動していました。

瞽女の規則「瞽女式目(ごぜしきもく)」

高田の瞽女たちは、「瞽女式目」と呼ばれる厳格な規則に従って生活していました。この規則は、おそらく1634年に徳川幕府に認可され、1692年に改訂された男性の盲人芸能者集団「当道(とうどう)」の全国組織による式目を手本にしていたと考えられます。当道の式目は、当初は江戸に限定されていましたが、次第に全国に広がり、按摩や漢方医学など幅広い活動も対象としていました。

瞽女式目は、瞽女の生活のあらゆる面――日常の生活習慣に至るまで――を網羅していました。これらの規則は毎年、「妙音講(みょうおんこう)」という法要の場で唱えられました。妙音講は音楽の女神・弁才天を祀る儀式であり、高田の瞽女にとっては年に一度、5月13日に高田寺町の天林寺で開催されていました(1939年まで続けられました)。

妙音講への出席は、旅からの適切な時期の帰還を求められることを意味しており、瞽女たちは「牡丹」の花の香りを感じ取ることで、その時期が近づいたことを知ったといわれています。

これらの規則を守ることは、瞽女たちの高い道徳的基準を維持するために重要であり、それ自体が一種の「守り」となっていました。重大な規律違反には、修行年数を減らすという厳しい罰則が科せられました。これは、年功序列が重視される瞽女社会において非常に重い処分でした。

最も重大な違反とされたのは、男性との関係を持つことであり、その内容によっては破門(追放)という厳罰に処されることもありました。

明治時代に入り、時代の変化や近代的な考え方に合わせるため、高田の瞽女たちは規則を見直し、1900年代初頭には「同業仲間」として、より職業的な組織へと移行しました。

最後の瞽女たち

徐々に消えていく伝統に終わりの時期を明確に定めるのは難しいものですが、瞽女の場合には特に象徴的な2つの名前と年が挙げられます。それは、1964年に杉本キクイが最後の巡業を終えたこと、そして1973年に小林ハルが巡業から引退したことです。幸いなことに、両者ともその後も演奏活動を続け、多くの音源が録音され、後世に残されました。

杉本キクイ

高田における最後の瞽女家元である杉本キクイは、1898年に現在の上越市東中島で生まれました。6歳で失明し、7歳のときに杉本家初代である杉本ませの弟子となりました。杉本家は高田市東本町4丁目にありました。1932年にませが亡くなった後、キクイが家元を継ぎました。

多くの瞽女たちが生活の変化によりその生き方を断念する中で、キクイは養女の静(しず)と補佐役の難波ことみとともに活動を続けました。彼女の最後の巡業は1964年、故郷の上越市東中島を訪れたときでした。

1970年にはその功績が認められ、黄綬褒章を受章。さらに1976年には重要無形文化財保持者(人間国宝)として認定されました。

1983年に85歳で亡くなりました。最期の言葉は、「唄の文句を忘れた。生きていてもしょうがない」だったと言われています。

小林ハル

最後の瞽女とされる小林ハルは、1900年に現在の新潟県三条市で生まれました。4歳のとき、樋口フジのもとで瞽女としての修行を始め、1915年には長岡のハツジサワに入門。ハツジサワの死後は坂井ツルに師事しました。33歳で正式な瞽女として認められます。

戦争や個人的な苦難を乗り越え、1973年に新発田の養護施設で引退。1977年には、旧瞽女などの盲人も受け入れる施設「やすらぎの家」(胎内市)に移りました。

引退後も自身の瞽女唄の録音に協力し、記録を後世に残すことに尽力しました。

1978年には人間国宝として認定され、翌1979年には黄綬褒章を受章しました。彼女には竹下玲子らの弟子がおり、萱森直子 (かやもりなおこ)が最後の弟子となりました。2005年、105歳で亡くなりました。

高田瞽女の生活における天林寺の役割

天林寺は、高田瞽女にとって精神的・共同体的な中心地として機能していました。ここは、瞽女たちが集い、儀式に参加する場所であり、彼女たちの共有するアイデンティティと目的を支える場でもありました。

瞽女たちにとって、音楽の守護神である弁財天は特別に崇拝されており、その信仰の中心が、高田寺町にある曹洞宗の寺院・天林寺でした。天林寺では、毎年5月13日に弁財天を祀る「妙音講(みょうおんこう)」という年中行事が行われており、高田のすべての瞽女がこの重要な行事に出席しました。

経が読まれ、弁財天への礼拝が行われたあと、「瞽女式目」と呼ばれる厳格な生活規則が読み上げられ、続いて演奏と宴が催されました。この妙音講は、瞽女にとって一年で最も重要な儀式でした。

この年中行事は1939年に一時中断されましたが、1972年に復活し、1980年まで毎年開催されました。その後、1983年に杉本キクイの死去直後に再び妙音講が執り行われ、その際には杉本シズと難波コトミが参加しました。

再び注目されるようになった瞽女(ごぜ)たち

20世紀初頭、日本全国で瞽女の伝統はほぼ姿を消していきましたが、皮肉なことに、その衰退とともに、その記録や保存に対する関心が高まっていきました。特に、長岡や高田といった地域では、瞽女の活動が20世紀中頃まで続いており、当時の日本では民俗文化の保存に対する意識が高まっていたこともあって、貴重な記録が残されることになりました。最後の世代の瞽女たちはまだ存命であり、インタビューや録音・映像記録を通じて、その音楽や生活が記録されることとなったのです。

この保存活動には、多くの芸術家や文化人たちが重要な役割を果たしました。その中には以下のような人物がいます:

- 画家・作家の斎藤真一

- 写真家の橋本照嵩と濱谷浩

- 小説家の水上勉(彼の小説『はなれ瞽女おりん』は、映画『はなれ瞽女おりん』(1977年)の原作となりました)

中でも最も重要な役割を果たしたのが、高田出身の市川慎二です。彼は「日本民俗学の父」と呼ばれる柳田國男の弟子であり、柳田の勧めを受けて、高田瞽女の研究を生涯の仕事としました。市川は多くの芸術家や研究者に瞽女文化への関心を呼び起こし、その保存に大きく貢献しました。彼の活動を支援したのが、実業家で慈善活動家でもある渋沢栄一の孫、渋沢敬三です。敬三は日本銀行総裁や大蔵大臣を歴任しながら、民俗学への強い関心を持ち、市川の活動を後押ししました。

音楽面での保存活動としては:

- 1953年に、民謡研究家で評論家の町田嘉章(まちだかしょう)が、柏崎の瞽女伊平タケを録音

- 1954年には、杉本キクイが『さいもん松坂』を録音

- 1969年、杉本は東京の国立劇場で公演

- 1975〜1979年にかけて、上越市で彼女のレパートリーの多くが録音された

- 小林ハルの最後の録音は1996年に行われた

こうした取り組みにより、瞽女の伝統は完全には失われず、今日もなお継承されています。現在では以下のような女性たちが、瞽女音楽の教授や演奏を行い、伝統の継承に努めています:

- 広沢里枝子(ひろさわりえこ)

- 萱森直子(かやもりなおこ)

- 小竹栄子(こたけえいこ)

- 室橋光枝(むろはしみつえ)

- 小方理恵(おがたりえ)

- 竹下玲子(たけしたれいこ)

- 月岡祐紀子(つきおかゆきこ)

- 横川恵子(よこかわけいこ)

- その他多数

彼女たちの活動によって、「音楽」「共同体」「規律」を通じて生きる意味と力を見いだした瞽女たちの力強い遺産は、今もなお語り継がれ、尊敬され続けています。

高田の瞽女ミュージアム(Goze Museum in Takada)

瞽女への関心の復興は、2015年に開館した高田の瞽女ミュージアムを中心に進められています。このミュージアムは、瞽女の歴史と文化を保存することを目的とした、日本で唯一の専門博物館です。

ミュージアムは、町家と呼ばれる伝統的な建物の中に設けられています。元々の麻屋高野 町家は1935年に焼失しましたが、1937年に元の間取りを再現して再建されました。2012年には国の登録有形文化財に指定されています。

館内の展示には、1970年代初頭に制作された当時存命中だった最後の瞽女たちの生活を記録したドキュメンタリー映像や、瞽女唄の録音、斎藤真一による瞽女絵画の数々、橋本照嵩らの写真作品などが含まれています。

ミュージアムの開館時間は週末の午前10時から午後4時までで、上越市高田・東本町1丁目2番33号に位置しています(www.goze-museum.com)。

Rie Ogata performing a goze song at the myoon-ko at Tenrinji, on May 10, 2025 (Photo: Kanoko Iwanami)