(英語の後に日本語が続きます。)

Joetsu’s history is dominated by the exploits of 16th century daimyo, Uesugi Kensin, during the period of the “Warring States”. The 16th century is far enough behind us to be able to ignore the terrible wars fought in those days but it is harder to ignore Joetsu’s role in the second world war, or Greater East Asia War (大東亜戦争).From 1942 to 1945 Naoetsu was home to the Tokyo POW Camp #4 branch. The camp gained a particularly poor reputation as regards treatment of its prisoners.

But let us start at the beginning.

At the beginning of the war, Japanese forces captured in total about 350,000 allied prisoners-of-war. About 36,000 military and civilian prisoners were subsequently transferred to Japan, allocated to 130 different camps and in most cases used as slave labour. At the end of the war 91 camps were still in operation. About 3,500 prisoners did not survive.

When Singapore surrendered on February 15, 1942, 50,000 British and Australian troops were imprisoned. Groups of these prisoners were subsequently moved to different locations in Japan and its occupied territories. One group of 563 Australians was shipped to Japan on November 29, 1942 on the “Kamakura Maru”, together with about 1,400 Dutch, US, and British prisoners, as well as Japanese civilians.

Upon arrival in Japan the Australians were split in two groups. One group went to Kobe, and the second group of about 300 men was sent to Naoetsu, where they arrived on December 10, 1942. Most of the men belonged to Infantry Battalion 2/20, some to Battalions 2/18 and 19.

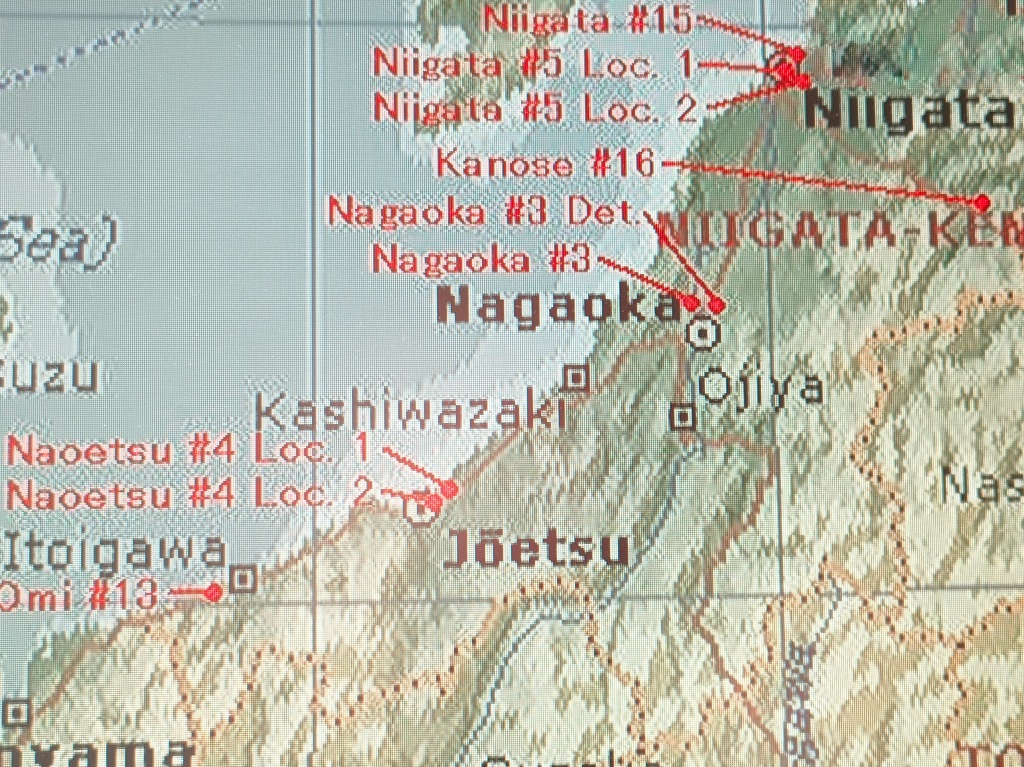

Niigata Prefecture suffered a severe labour shortage resulting from the military draft. Niigata companies had therefore requested the government in Tokyo to explore the possibility of using POWs as forced laborers. The headquarters of the Tokyo Horyo Shuyojo (Tokyo POW Camps) established 7 branch camps in Niigata Prefecture. The Naoetsu camp (#4B) was opened in a facility of Shin-etsu Chemical Company.

The Naoetsu Camp

Initially the prisoners were put to work for Shin-etsu Chemical and for Nippon Stainless Steel, later adding Nippon Soda and two transportation companies.

On April 2, 1943 the prisoners were moved to Kasuga-shinden, Arita-mura, Nakakubiki-gun, what is now Kawara-machi, Joetsu.

During the course of 1943, prisoners had started dying as a result of malnutrition, exhaustion and abusive treatment. The first man to die at Naoetsu, on March 31, 1943 was Andrew Robertson, the most senior officer of the group.

At the end of the year 28 prisoners had died. The high fatality rate had raised questions in Tokyo and the commanding general of Tokyo Horyo Shuyojo visited Naoetsu in February 1944. At that point a total of 54 prisoners had died, many suffering from beri-beri and pneumonia.

After the inspection visit from Tokyo, treatment of the prisoners improved. Medical care and food rations improved but the men continued to be used as forced labor. Officers were allocated jobs in the camp but were free from hard labor. The different treatment generated tension between officers and men.

Camp life became gradually more tolerable and the last (60th) Australian fatality was on August 24, 1944.

At the end of March 1944 an additional group of US, British and Dutch POWs were sent to the Naoetsu camp, increasing the total occupation of the camp to well over 600. Overcrowding created its own problems and did little to stimulate a good relationship between the Australians and the newcomers.

On VJ-day, August 15, 1945 there were 698 prisoners in the camp. In addition to 231 Australians, there were 338 Americans, 90 British and 39 Dutchmen.

After the war ended

As soon as the war ended, the camp administration in Tokyo issued detailed instructions how to deal with POWs.

These orders provided for full protection to all POWs, maintenance of hygiene standards, adequate food supply, distribution of clothing, medication and food sent by allied countries. Most importantly, they instructed the camps to cease the use of POWs as laborers. Finally, they instructed the camps to incinerate all unnecessary documents. These instructions significantly complicated efforts by the occupation authorities to reconstruct the whereabouts and status of former prisoners-of-war, as well as to gain insight in what transpired in the camps during the war years.

The Australian POWs left Naoetsu for Tokyo on September 5, 1945. They carried with them the boxes containing the ashes of their 60 fellow prisoners who died in Naoetsu. In January 1945 these boxes had been transferred from the camp to the Buddhist temple Kakushinji. Its head priest, Fujito Enri-san wished to make sure that these ashes were kept safe in an appropriate and dignified place.

Did the Geneva Convention apply and was it upheld?

International law relating to the treatment of prisoners of war was at the beginning of the Pacific War based on the 1929 Geneva Treaty on the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Japan had signed but did not ratify the treaty due to internal opposition from the Army, Navy and Privy Council.

In December 1941, the US government issued a statement expressing the hope that in the event of hostilities the Geneva treaty would be “mutually applied.” It was followed by similar statements from the governments of England, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Japan’s Foreign Ministry held a meeting on 21 January 1942 with representatives of the Army Ministry, the Police Department and the Overseas Development Ministry. Their recommendation was that “every effort should be made to correspondingly apply the provisions of the treaties regarding any prisoners of enemy countries that fall under the authority of Japan, including issues such as food, clothing, and the treatment of the prisoners in accordance with internationally recognized standards of human rights.” The Vice-Minister for the Army informed his counterpart of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs: “While we cannot proclaim our open support for the (Geneva) Convention, we have no objections to measures taken with regard to the treatment of prisoners of war.”

In a statement Foreign Minister Togo then confirmed that the Geneva Convention would take precedence over domestic laws and regulations that came into conflict with its provisions.

These statements may have signified good intentions but when in April of the same year the treatment of POWs was debated for the first time in the Bureau Heads Meeting of the Army Ministry, a new set of regulations for the treatment of prisoners of war was adopted. It was at this time that the Japanese military also decided that Caucasian prisoners would be useful in replenishing labor shortages on the Japanese side, in occupied territories as well as in Japan. In February 1943 the Foreign Ministry accordingly issued a statement that POWs could and would engage in “non-hazardous labor.”

Yokohama war trials

From reading diaries of former POWs, it is clear that their experiences differed from one camp to the next. An important factor often was the quality and effectiveness of Japanese camp management. Treatment of POWs in Naoetsu under first camp commander Sakata was relatively humane. After he was transferred though, conditions in the camp rapidly deteriorated, claiming the lives of 60 members of the 2/20th Battalion through disease, starvation, and the brutality of the guards. A greater percentage of men died at Naoetsu than in any other prisoner-of-war camp in Japan. The later Naoetsu camp commanders (Ota, Ishikawa) bore a heavy responsibility in this regard. Camp commanders were held directly responsible for what happened in the camps. There is a question of course to which extent responsibility for war crimes lies in first instance with the individuals who committed them, or with those indirectly involved, for instance in planning, decision making or organization. In Japan’s case ultimate responsibility was with the Army Ministry. It should also be recognized that the matter of prisoners did not sit high on the Ministry’s priority list. The camps were often managed and run by men who lacked training and qualifications for this purpose.

The decision to use Caucasian POWs, in addition to Korean and Chinese civilians, as slave labor — to address the labour shortages that started to occur in Japan from 1942 – was one taken at the highest level, at the Military Bureau of the Army Ministry. Their decision was in contravention of the provisions of the 1929 Geneva Convention (not ratified by Japan).

Fifteen of Naoetsu’s military and civilian guards were prosecuted for war crimes. They were classified as Class B or C war criminals, defined as “perpetrators of war crimes and those who abetted or permitted them”. All were found guilty; 7 received prison sentences and 8 the death sentence. In terms of convictions, Naoetsu rated worse than any other camp in Japan.

The executions provided closure to no one, not to the former POWs but also not to the families of the executed men. The camp and its aftermath remained a sensitive subject in Joetsu.

It is too easy to explain the war crimes tribunal away as “victor’s justice”. Real crimes against at least the spirit of existing treaties and against humanity were committed.

The party that is victorious in a conflict will always claim that justice is on its side. Determination who is victorious is difficult. A victor one day may be vanquished the next as reflected in the outcome of the Pacific War. In reality of course, war knows no victors, only losers.

Does anything remain of the camp, physically or in the form of a collective memory?

Did the citizens of Naoetsu know about the conditions in the camp and the atrocities committed there? If they did, the military would have made sure that the subject was not brought out in the open.

Could they have done anything about it had they known? Highly unlikely, because the military exercised total control and could not under any circumstances be overruled, at least not until the Emperor took the initiative to declare the war over on August 15, 1945.

This changed of course after the war ended. Although the country generally became focused on its reconstruction, Japanese prisoners of war returned from abroad and their families, and especially families of Japanese convicted of war crimes were sometimes ostracized, which is an often overlooked but tragic aspect of Japan’s post-war history.

We are inclined to let wartime memories fade away. However, efforts on the part of citizens of Naoetsu and former POWs have given us the opportunity to know and learn from the past and to pass lessons learned on to following generations.

The Naoetsu camp no longer exists. At its former location the Peace Memorial Park has been established, consisting of a building housing a small museum and meeting rooms for activities related to the keeping the camp memory alive, cenotaphs for the Australian and Japanese victims and a peace memorial sculpture. For a more detailed description of the Peace Memorial Park, how it came into existence and how and why Naoetsu connected with Cowra, NSW, Australia, please see my posts “Peace Memorial Park, Naoetsu” and “The Cowra Breakout”.

Museum and meeting rooms

直江津捕虜収容所

上越の歴史といえば、16世紀「戦国時代」に活躍した大名、上杉謙信が有名である。16世紀の悲惨な戦の記憶は遠い昔のことだが、第二次世界大戦 (又の名を大東亜戦争)の中で上越が担った役割は無視できない。1942年から1945年まで、直江津には東京捕虜収容所第四分所があった。この収容所は捕虜の扱いに関して特に評判が悪かった。

戦争が始まった当初、日本軍は合計で約35万人の連合軍捕虜を捕らえた。その後、軍人と民間人の約3万6千人が日本に移送され、130の捕虜収容所に振り分けられた。彼らはほとんどの場合、強制労働に従事させられた。終戦時には、91の収容所がまだ稼動していた。約3,500人の捕虜が収容所で亡くなった。

1942年2月15日のシンガポール降伏時、5万人の英軍とオーストラリア軍が収監された。これらの捕虜の集団は、その後、日本とその占領地域の各地に移送された。1942 年 11 月 29 日、オーストラリア人 563 人の捕虜は、オランダ、米国、英国の捕虜約 1400 人と共に「鎌倉丸」で日本へ移送された。

日本に到着したオーストラリア兵は、2つのグループに分けられた。一つのグループは神戸へ、約300人からなるもう一つのグループは直江津へ送られ、1942年12月10日に到着した。ほとんどの隊員は2/20歩兵大隊に所属し、一部は2/18と19大隊に所属していた。

徴兵制の影響により深刻な労働力不足に陥っていた新潟県企業は、東京政府に捕虜を強制労働者として利用する可能性を探るよう要請していた。東京捕虜収容所本部は、新潟県内に7つの分屯地を設置し、直江津収容所は、信越化学工業の施設内に開設された。

直江津捕虜収容所

最初は信越化学工業と日本ステンレスで、後に日本曹達と運送会社2社が加わり、働かされることになった。

1943年4月2日に捕虜たちは中頸城郡有田村春日新田(現在の上越市河原町)に移された。

1943年に入ると、栄養失調、過労、虐待などにより、捕虜の死が目立ち始めた。直江津収容所で最初に亡くなったのは、1943年3月31日、グループの最高幹部だったアンドリュー・ロバートソンだった。

この年の終わりには、28人の捕虜が死亡していた。この死亡率の高さに東京では疑問の声が上がり、1944年2月、東京捕虜収容所司令官が直江津を視察した。その時点で54名の捕虜が死亡しており、その多くが脚気や肺炎を患っていた。

視察後、医療や食料の配給等については改善されたが、強制労働は続いた。将校は、収容所内で仕事を割り当てられたものの重労働は免れた。将校とその他の捕虜への待遇の違いが互いに緊張感を生む結果となった。

収容所の生活は次第に耐えられるようになり、最後の(60 人目の)オーストラリア人捕虜の死亡者 が出たのは 1944 年 8 月 24 日のことであった。

1944年3月末、直江津収容所には米国、英国、オランダの捕虜が追加で移送され、収容所の総人員は600人を大きく上回 った。収容所の過密状態はそれ相応の問題を引き起こし、オーストラリア人捕虜と新入りの捕虜の間に良好 な関係が生まれることはほとんどなかった。

1945 年 8 月 15 日の 終戦記念日には、直江津収容所には 698 人の捕虜がいた。オーストラリア人 231 人のほか、アメリカ人 338 人、イギリス人 90 人、オランダ人 39 人がいた。

終戦後

戦争が終わるとすぐに、東京の収容所管理局は、捕虜の扱いについて詳細な指示を出した。

これらの指示は、すべての捕虜の完全な保護、衛生状態の維持、同盟国から送られた衣服、薬、食料の分配を規定しており、最も重要なことは、捕虜の労働力としての使用を辞めさせるよう指示した事だった。そして最後に、保管されていた不要な書類をすべて焼却するよう指示した。これらの指示は、戦時中の収容所での出来事を把握しようとしていた占領当局の努力を著しく困難にした。

オーストラリア兵捕虜は1945年9月5日、直江津から東京へ向かった。捕虜収容所で死亡した60人分の遺灰も一緒だった。これらの遺灰は1945年1月、尊厳を持って遺灰を安置することを望んだ藤戸円理住職により覚真寺に安置されていた。

ジュネーブ条約は適用され、支持されたのか?

捕虜の扱いに関する国際法は、太平洋戦争当初は1929年の「捕虜の処遇に関するジュネーブ条約」に基づいていた。日本はこの条約に署名はしたものの、陸海軍や枢密院の内部反対により批准はしていなかった。

1941年12月、アメリカ政府は、敵対行為の際にはジュネーブ条約が「相互に適用される」ことを望むという声明を発表した。その後イギリス、カナダ、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドの各政府も同様の声明を出した。

外務省は1942年1月21日、陸軍省、警察庁、海外開発庁の代表者と会議を開いた。その提言は、「日本の管轄下にある敵国の捕虜については、食料、衣類、国際的に認知された人権基準に従った捕虜の処遇などの問題を含め、条約の規定を相応に適用するようあらゆる努力をすること」であった。陸軍次官は、外務省の担当者に「ジュネーブ条約への支持を公言することはできないが、捕虜の待遇に関する措置に異存はない」と伝えた。

その後、東郷外相は声明の中で、ジュネーブ条約の規定に抵触する国内法令にはジュネーブ条約が優先されることを承認した。

しかし、同年4月の陸軍省局長会議で初めて捕虜の待遇が議論され、新しい捕虜待遇規則が採択された。このとき日本軍は、日本側の占領地や国内での労働力不足を補うために、白人捕虜が有用であると判断したのである。外務省は1943年2月、捕虜は「非危険労働」に従事することができ、また従事することになるという声明を発表した。

横浜裁判

元捕虜の方が書いた日記を読むと、それぞれの収容所によって体験が異なる事がよくわかる。多くの場合、重要な要因は、日本の各収容所の管理運営の質と効果であった。直江津の坂田初代収容所長のもとでの捕虜の扱いは、比較的人道的であった。しかし、彼の転任後、収容所の状況は急速に悪化し、病気、飢餓、看守の残忍行為により60人の命が奪われた。直江津は、日本の他のどの捕虜収容所よりも死者の割合が多かった。この点では、後の直江津収容所長(太田、石川)が大きな責任を負っている。収容所長は、収容所で起こったことに直接責任を負っていた。もちろん、戦争犯罪の責任は、それを犯した個人にあるのか、それとも、計画、意思決定、組織化など間接的に関与した人々にあるのか、という問題はある。日本の場合、最終的な責任は陸軍省にあった。また、捕虜に関する問題は陸軍省にとって優先順位の高いものではなかったことも認識されるべきである。収容所の管理運営は、訓練も資格もない人たちが行うことが多かったのである。

1942年から始まった日本の労働力不足に対応するため、朝鮮人や中国人に加え、白人捕虜を強制労働に使うという決定は、陸軍省軍事局の最高レベルでなされたものである。この決定は、1929年のジュネーブ条約(日本は未批准)の規定に反するものであった。

直江津の軍人、軍属の看守15人が戦争犯罪で起訴された。彼らは、「戦争犯罪の加害者とそれを教唆または許可した者」と定義されるB級またはC級戦犯に分類された。全員が有罪となり、7人が実刑、8人が死刑となった。有罪判決という点では、直江津は日本の他のどの収容所よりも悪い評価だった。

この出来事は、元捕虜だけでなく、処刑された人たちの家族にも、誰にも戦争の終結をもたらすことはなかった。収容所とその余波についての出来事は、上越では依然としてデリケートな問題である。

戦争犯罪法廷を「勝者の正義」と説明するのはあまりに簡単である。少なくとも既存の条約の精神に反し、人道に反する犯罪が行われたことは事実である。

戦争で勝利した当事者は、常に正義は自分の側にあると主張するが、誰が勝者であるかを決定するのは難しい。太平洋戦争の結末に見られるように、ある時点で勝利した者が次の日には敗北しているかもしれないのだ。現実には、戦争に勝者はなく、敗者のみが存在する。

収容所の跡地に記憶として残るもの

直江津市民は、収容所の状況やそこで行われた残虐行為を知っていたのだろうか。たとえ知っていたとしても、軍はその話題を表に出さないようにしただろう。

少なくとも1945年8月15日に天皇が終戦を宣言するまでは、軍部が完全に支配し、どんなことも軍部を覆すことはできなかったからだ。

しかし、戦争が終わるとそうはいかなくなる。国は復興に力を注ぐようになったが、外国から帰ってきた日本人捕虜とその家族、とりわけ戦争犯罪で有罪判決を受けた日本人の家族は、世間から排斥される事が多々あった。これは、日本の戦後史の見落とされがちな、悲劇的な一面である。

私たちは、戦時中の記憶を風化させる傾向にある。しかし、地元の人や元捕虜の方々の努力によって、私たちは過去に起こった出来事から学び、次の世代に教訓を伝えていく事が出来るのである。

直江津収容所が建っていた場所には現在、平和記念公園があり、小さな博物館と活動のための部屋がある建物、オーストラリア人と日本人犠牲者のための慰霊碑、平和友好像が設置されている。平和記念公園について、また、直江津とオーストラリア・ニューサウスウェールズ州カウラ市の関係については、「平和記念公園、直江津」「カウラ大脱走」の記事をご覧ください。

Pingback: The COWRA BREAKOUT – JOETSU STORIES